System and method for cleaning noisy genetic data and determining chromosome copy number

a genetic data and chromosome technology, applied in the field of genetic data acquisition, manipulation and use, can solve the problems of noisy m2 trisomy, high error-prone direct measurement of dna, unregulated current pgd techniques,

- Summary

- Abstract

- Description

- Claims

- Application Information

AI Technical Summary

Benefits of technology

Problems solved by technology

Method used

Image

Examples

Embodiment Construction

Conceptual Overview of the System

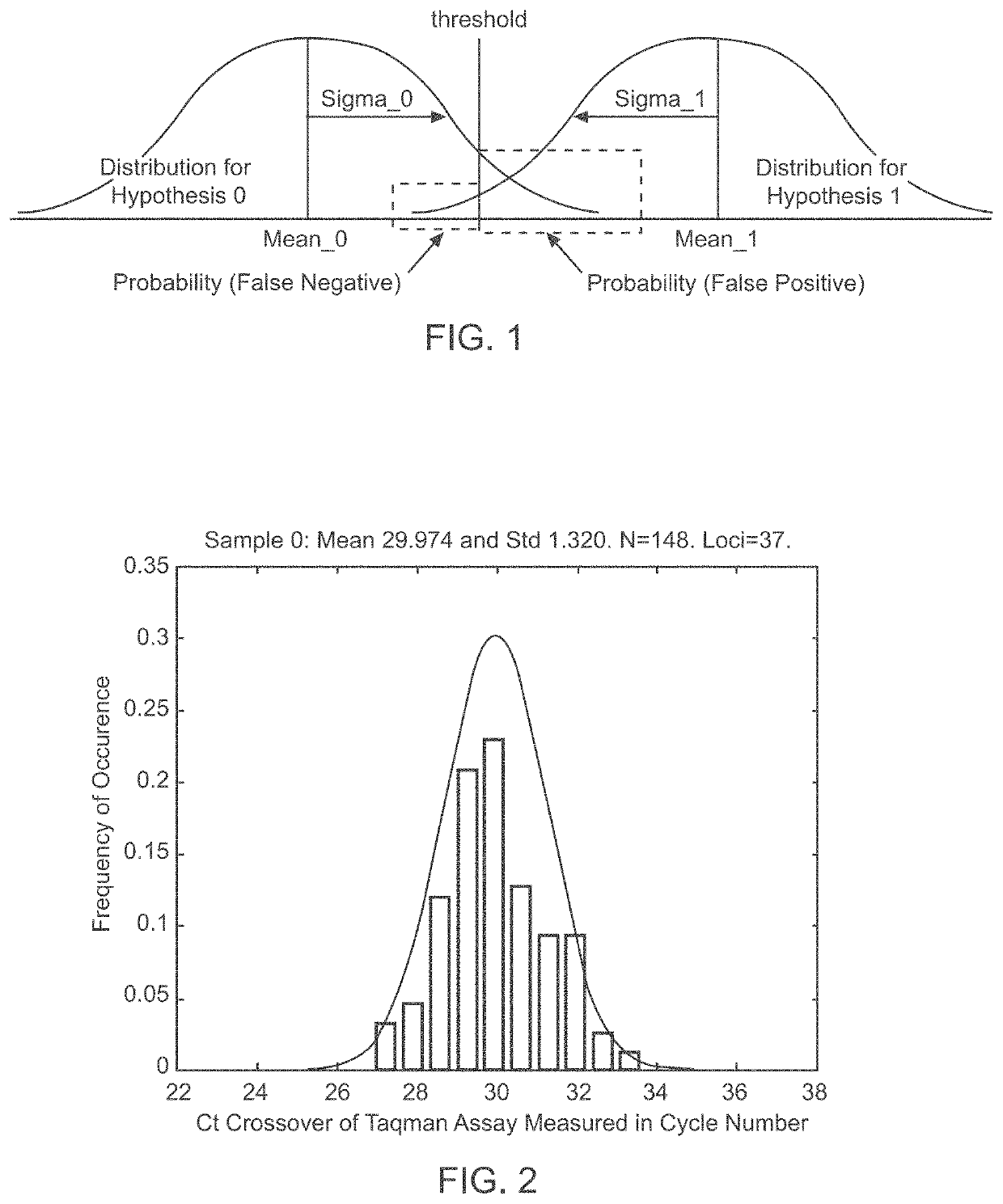

[0060]The goal of the disclosed system is to provide highly accurate genomic data for the purpose of genetic diagnoses. In cases where the genetic data of an individual contains a significant amount of noise, or errors, the disclosed system makes use of the expected similarities between the genetic data of the target individual and the genetic data of related individuals, to clean the noise in the target genome. This is done by determining which segments of chromosomes of related individuals were involved in gamete formation and, when necessary where crossovers may have occurred during meiosis, and therefore which segments of the genomes of related individuals are expected to be nearly identical to sections of the target genome. In certain situations this method can be used to clean noisy base pair measurements on the target individual, but it also can be used to infer the identity of individual base pairs or whole regions of DNA that were not measur...

PUM

| Property | Measurement | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| fluorescent in situ hybridization | aaaaa | aaaaa |

| electrophoresis | aaaaa | aaaaa |

| fluorescent PCR | aaaaa | aaaaa |

Abstract

Description

Claims

Application Information

Login to View More

Login to View More - R&D

- Intellectual Property

- Life Sciences

- Materials

- Tech Scout

- Unparalleled Data Quality

- Higher Quality Content

- 60% Fewer Hallucinations

Browse by: Latest US Patents, China's latest patents, Technical Efficacy Thesaurus, Application Domain, Technology Topic, Popular Technical Reports.

© 2025 PatSnap. All rights reserved.Legal|Privacy policy|Modern Slavery Act Transparency Statement|Sitemap|About US| Contact US: help@patsnap.com