Whichever method is used, the operator hopes to be in the immediate vicinity to the nerve (which is necessary for reliable nerve blocks) and not in the nerve itself (which may result in traumatic

nerve injury when the

local anesthetic is injected into the nerve).

Consequently, with these three described methods for localizing nerves during nerve blocks, the needle tip may inadvertently be inserted into the nerve itself.

However, one of the major disadvantages of regional

anesthesia and nerve blocks in particular is the possibility of nerve damage during administration of nerve blocks or regional

anesthesia.

Other drawbacks include the risks of systemic and local toxic complications.

Thus, it may not be surprising that the most common and troublesome local complications of nerve blocks and regional anesthesia involve the

peripheral nerves.

Such complications are, fortunately, rare, but they can cause considerable problems for both patient and physician.

Of note, even the most careful anesthesiologist will occasionally encounter a PNS complication.

While the overall incidence of nerve damage after nerve blocks is relatively low, the consequences can be catastrophic and result in a temporary or permanent injury to the nerve, loss of limb function and

paralysis.

This in turn may result in either mechanical trauma to the nerve,

ischemic injury to the nerve due the

resultant increase in endoneural pressure due to the high pressures inside the nerve, and / or endoneral

edema.

During this period, the nerve fascicle is both ischemic and vulnerable to otherwise toxicologically neutral local

anesthetic solutions.

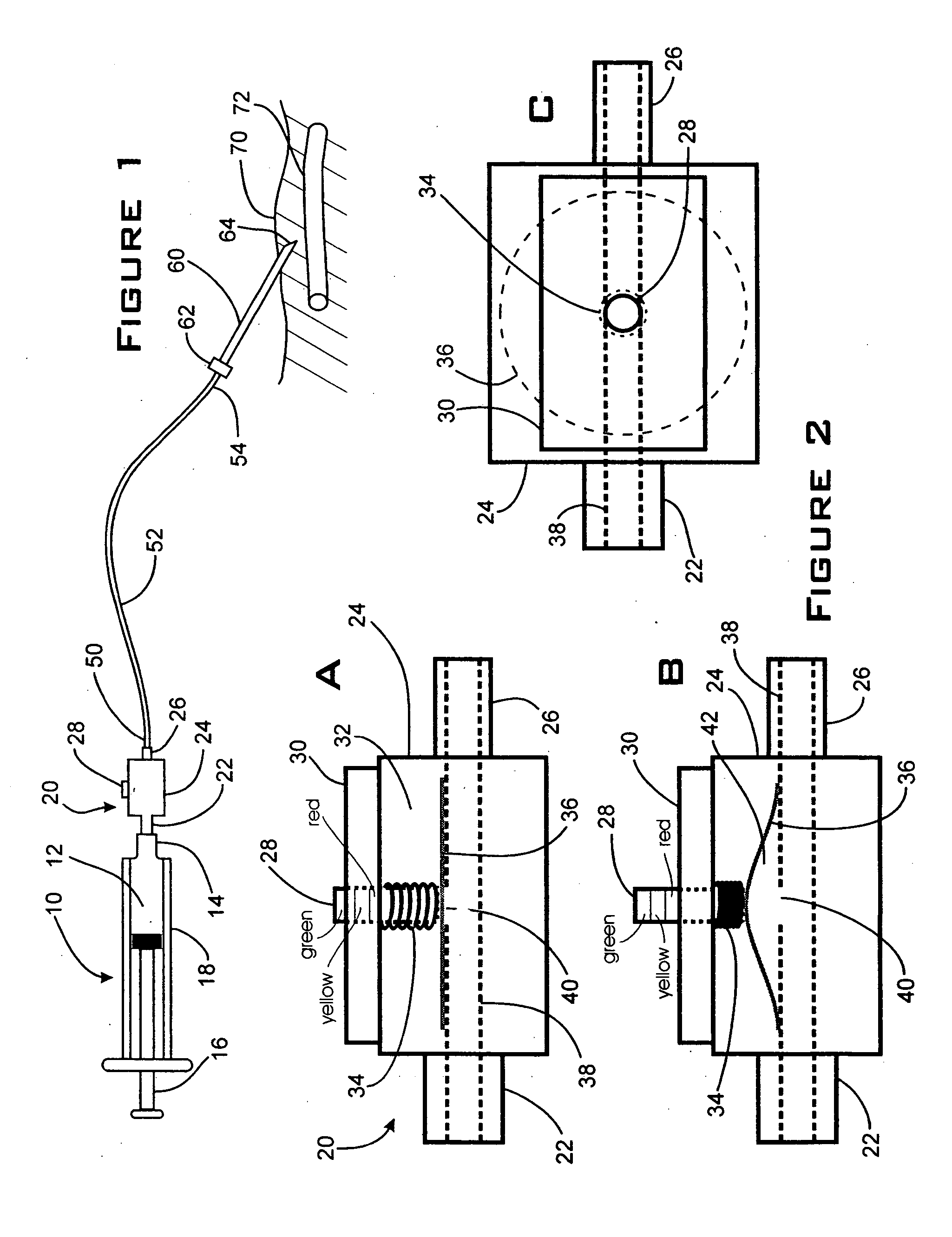

However, these judgments are prone to subjective interpretation and / or the “feel” of the operators and not on any objective measurements (e.g., measured

injection pressure, speed, or similar variables).

The ability of different operators to estimate and / or control the injection (especially as with regard to pressure) is further complicated by differences in

hand strength and experience among operators as well as differences in resistance to injection for various needle types, lengths, and lumen calibers.

This practice poses a risk of exerting too high pressures during injection and possible unrecognized intraneuronal injection.

In addition, the operator typically uses both hands to perform the procedure (i.e., place the injection needle in the appropriate location relative to the nerve) and cannot easily determine and / or control the amount of force and pressure that the assistant may employ to inject the local

anesthetic.

Moreover, forceful and / or fast injections of local anesthetic solutions can lead to a higher risk of systemic local anesthetic

toxicity (e.g., seizures, arrhythmia, cardiovascular collapse, and death) due to tracking of local anesthetic between tissue

layers and inadvertent intravascular injections.

Additionally, intraneuronal and rapid injections of local anesthetics can backtrack to the

spinal column and result in unintended epidural or

spinal anesthesia with potentially disastrous consequences (Selander et al., “Longitudal Spread of Intraneurally Injected Local Anesthetics,” Acta Anesth. Scand., 22, 622 (1978); Tetzlaff et al., “Subdural

Anesthesia as a Complication of an lnterscalene Brachial

Plexus Block,” Regional

Anesthesia, 19, 357-359 (1994); Dutton et al., “Total

Spinal Anesthesia after Interscalene

Blockade of the Brachial

Plexus,”

Anesthesiology, 80, 939-941 (1994)).

None of these attempts, however, focused on controlling and / or measuring the pressure and / or injection speed during injection to avoid an inadvertent intraneuronal injection, or rapid spread, and / or absorption of local anesthetics during

nerve blockade / regional anesthesia.

Login to View More

Login to View More  Login to View More

Login to View More