Method, Implant & Instruments for Percutaneous Expansion of the Spinal Canal

- Summary

- Abstract

- Description

- Claims

- Application Information

AI Technical Summary

Benefits of technology

Problems solved by technology

Method used

Image

Examples

Embodiment Construction

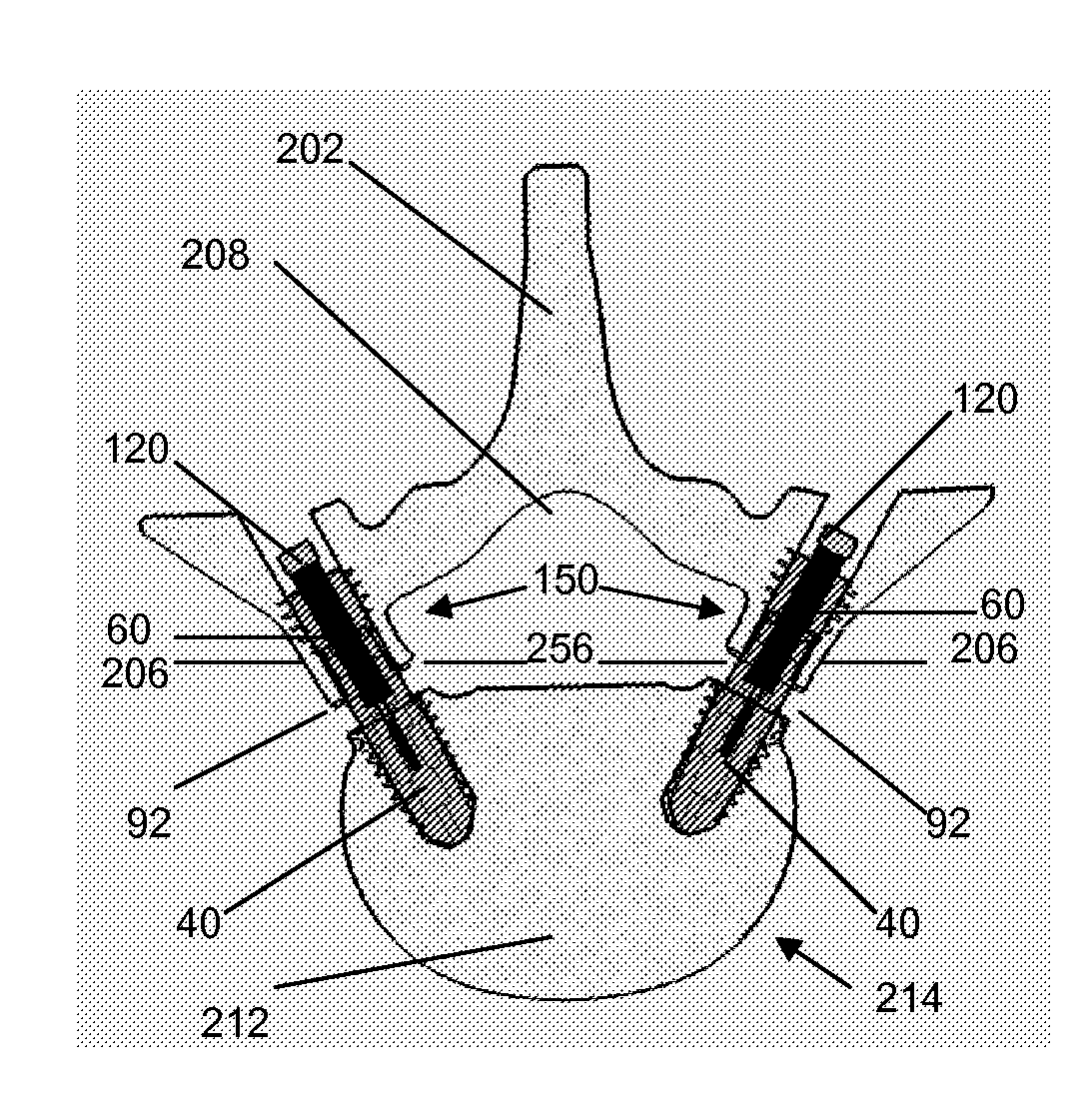

[0101]Referring now to the drawings, where like numerals indicate like elements, there is shown in FIGS. 1A-1C, a top view 1A, side view 1B, and cross-sectional view 1C, of a lower or distal shell portion 10 of a pedicle lengthening implant of the present invention. The lower implant shell 10 has outer threads 2 and hollow inner spaces 8, 12, along with side wall slots 4 and a cannulation hole 6.

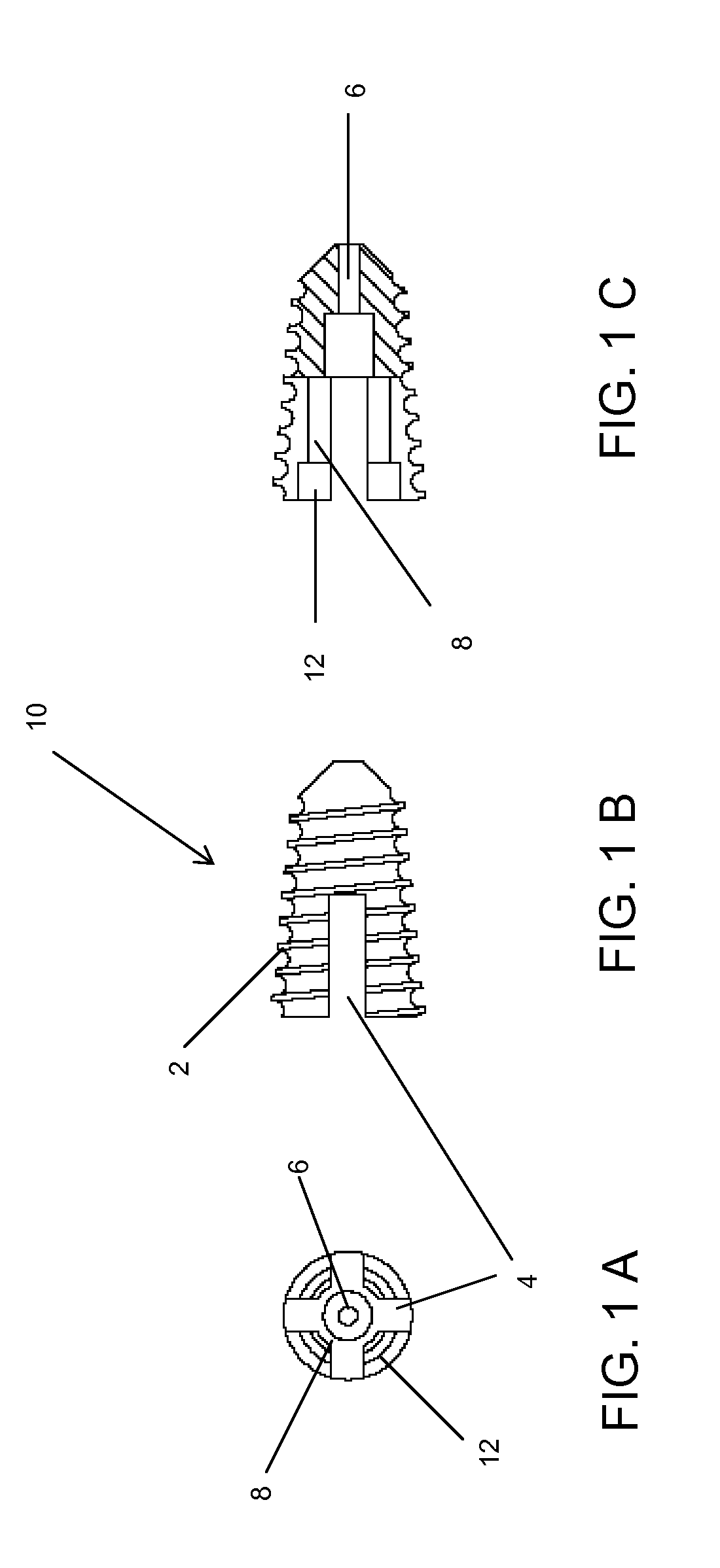

[0102]FIGS. 2A1-2D2 comprises lower implant components, including the lower implant shell 10, a floating nut 20 and a locking ring 30. The locking ring 30 is shown in cross-section, and by top view, in FIGS. 2A1 and 2A2, respectively. The locking ring 30 comprises a substantially circular shape and has a central passage 22. The floating nut 20 is shown in cross-section and by top view in FIGS. 2B1 and 2B2, respectively. The floating nut 20 contains a plurality of flanges 18 on its' outer surface, and a tapered entrance 16 to an inner threaded portion 14.

[0103]An assembled lower implant porti...

PUM

Login to View More

Login to View More Abstract

Description

Claims

Application Information

Login to View More

Login to View More - R&D

- Intellectual Property

- Life Sciences

- Materials

- Tech Scout

- Unparalleled Data Quality

- Higher Quality Content

- 60% Fewer Hallucinations

Browse by: Latest US Patents, China's latest patents, Technical Efficacy Thesaurus, Application Domain, Technology Topic, Popular Technical Reports.

© 2025 PatSnap. All rights reserved.Legal|Privacy policy|Modern Slavery Act Transparency Statement|Sitemap|About US| Contact US: help@patsnap.com