The difficulty arises, however, in that the

handwriting is often messy, illegible, or incomplete, and can lead to incorrect fulfillment by the dispensing

pharmacist.

Furthermore, the current way in which a physician writes a prescription is also accompanied by another difficulty encountered when the physician gives the patient samples of the

drug to be dispensed.

This approach to providing complimentary pharmaceuticals can further introduce problems into the whole prescription provision process.

For example, samples may be lost or stolen at a doctor's office, or may become old or expired.

Other times, it may simply be inconvenient for physicians to use samples in their daily practice because of storage space and temperature requirements, or because it is distracting and inefficient to retrieve the samples in the course of a hectic day.

Lastly, the current approach to providing prescription medicines is further complicated by the epidemic problem of compliance with the terms of the prescription.

Simply put, samples are only one-time inducements to take a medication in the beginning of a

treatment regimen, and do not offer ongoing incentives for patients, especially for those patients who are concerned about medication costs and may not refill the prescription.

This dynamic in the current prescription fulfillment process is particularly unfortunate: non-compliance in

prescription drug taking is putting an enormous strain on the health care

system today.

Other results of non-compliance include hospital and

nursing home admissions, as well as lost wages and lower productivity.

Moreover, the most pressing aspect of non-compliance is reflected in the fact that compliance drops off dramatically when it comes time to refill a prescription.

This represents an unhealthy dynamic that greatly costs both employers, insurance companies, and society at large, over time.

In addition, as prescription drugs become more expensive, and as government and employer funded coverage for such

drug plans becomes less comprehensive, compliance becomes even more so of a concern for doctors who are concerned about their patients following through with treatments, as well as for insurance companies who wish to reduce the resulting costs of non-compliance, and also for patients who yearn for a less expensive form of compliance.

As such, prior art systems do not address the root of the problem in non-compliance, which is motivation, something which is often compromised by ongoing financial concerns associated with prescription fulfillment.

While these systems may attempt to provide some form of compliance, none actually encourage or motivate a patient through financial incentives to comply with a

drug prescription on a sustainable basis.

Accordingly, no prior art

system exists to assure realistic, long-term compliance in the taking of prescription drugs.

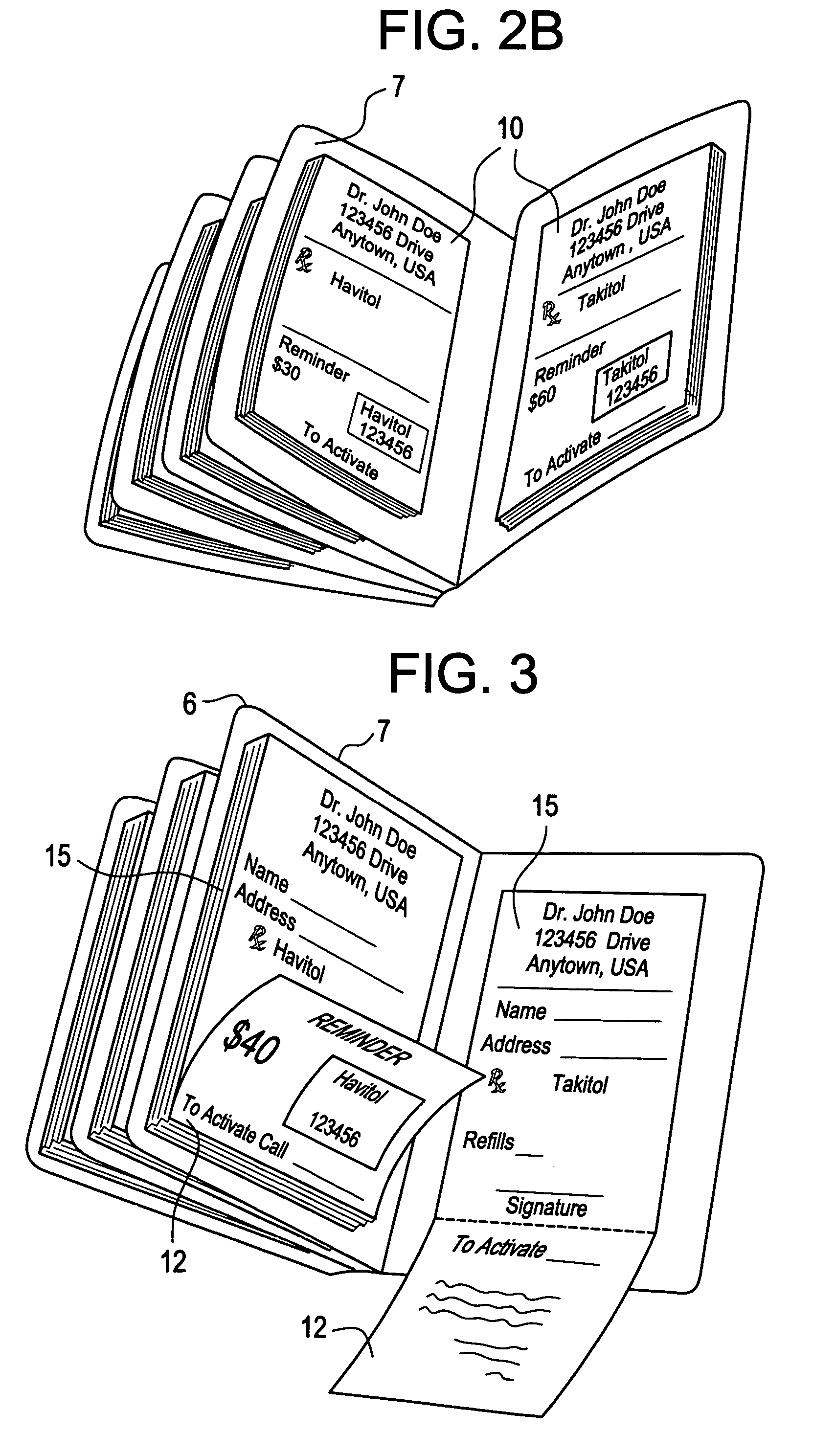

Particularly, none of these systems provide both a means of notification and an incentive for a given prescription medication to be taken.

Moreover, there is a particular problem with distributing such systems to patients.

Without offering a convenient implementation to a physician, some doctors may tend to forget or otherwise

neglect to offer patients such systems.

Similarly, without ease of use and significant incentivization, patients will not accept such distributions from doctors, or otherwise will not regularly utilize them, thereby making the problem difficult at both ends of distribution.

In total, no

system exists to address the combined shortcomings of error-prone handwritten prescriptions, inefficient sample distribution, and the lack of assurance of long-term compliance in the taking of prescription drugs.

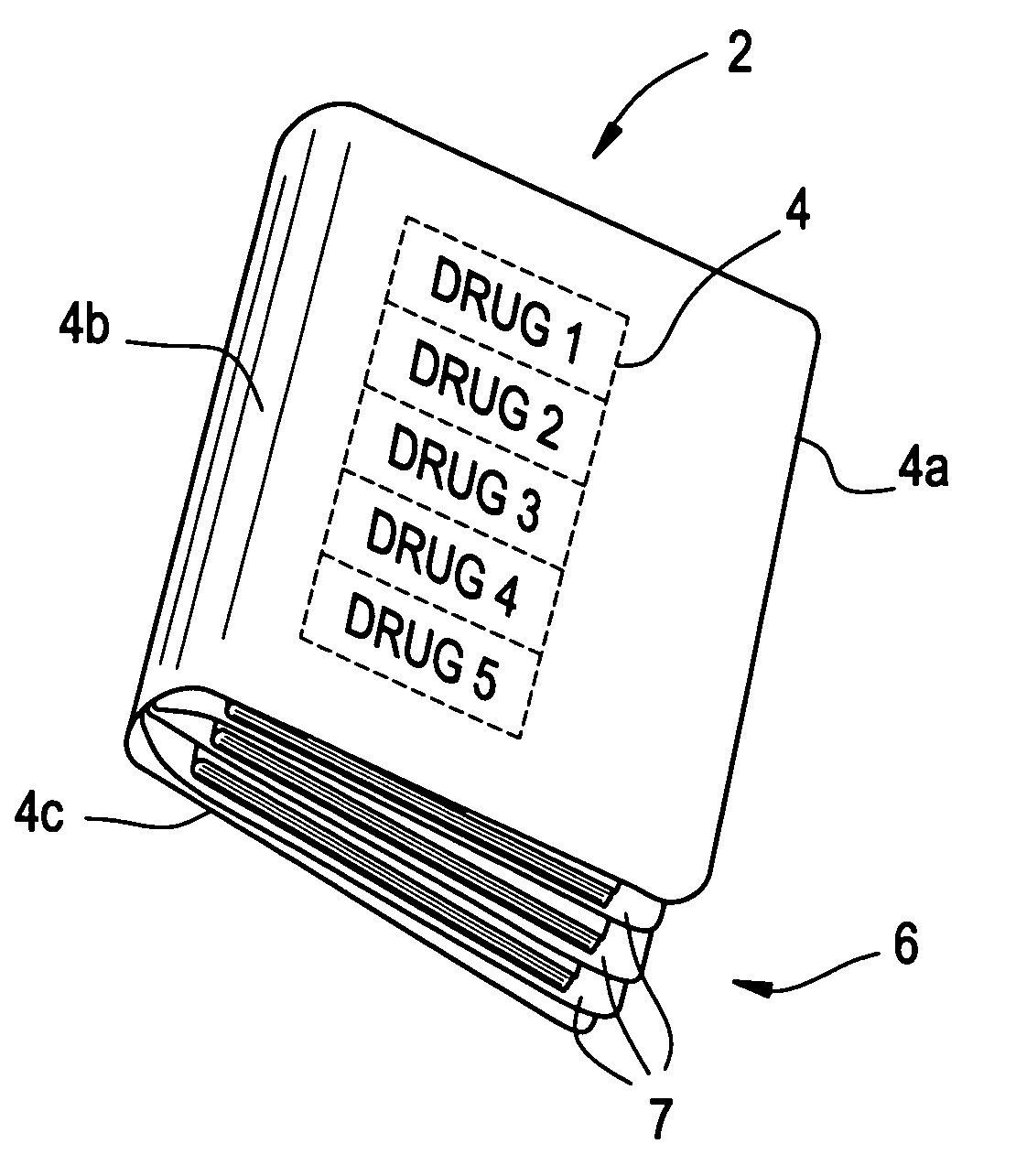

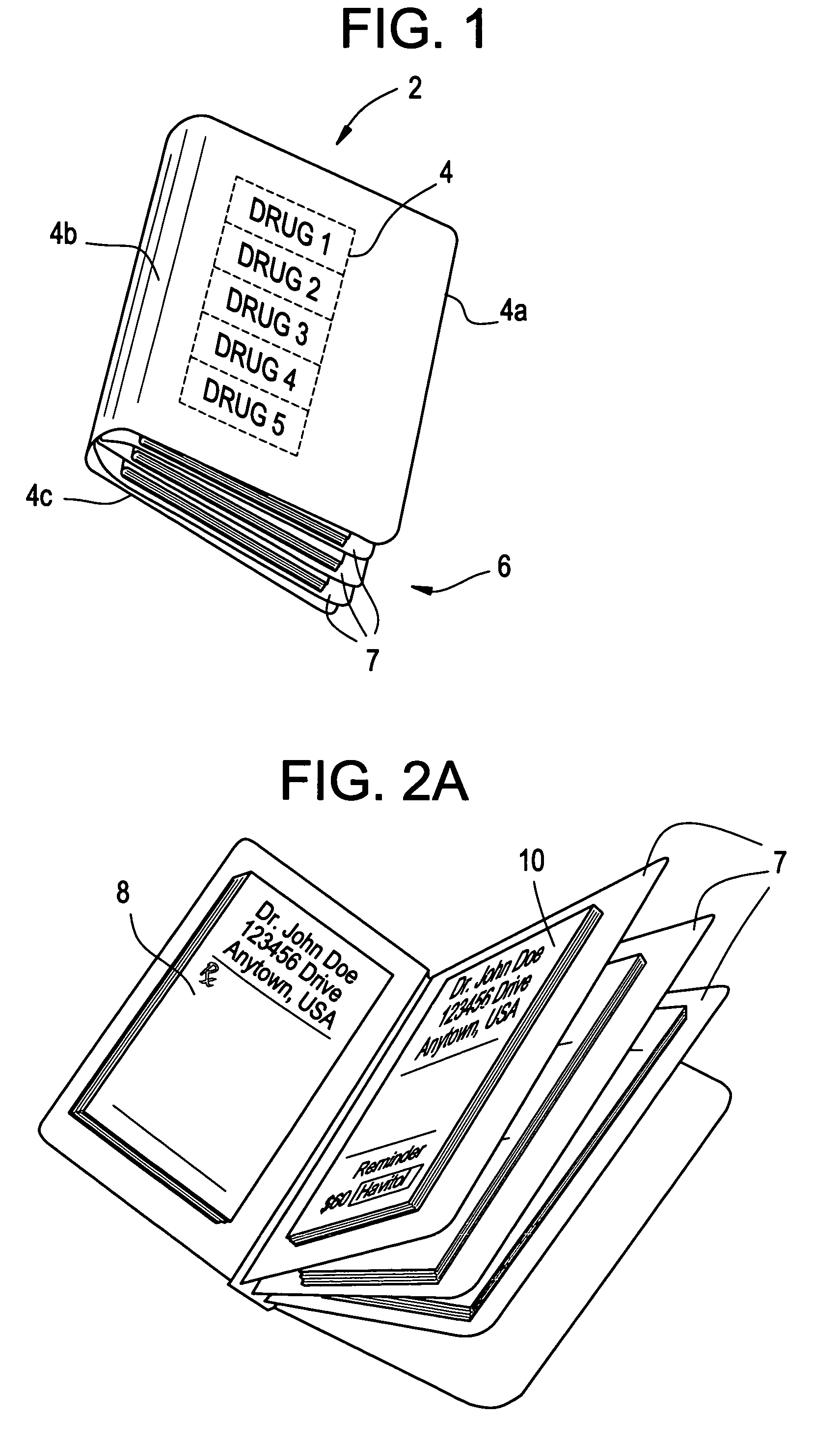

Moreover, no system offers solutions to all of these problems and means to motivate doctors to use a given system on a daily basis, by providing a simplified way of error free prescription writing that is practical, compact and convenient to carry around on their person throughout the day.

Login to View More

Login to View More